Is it possible that most popular programming languages lack the most efficient synchronization mechanism? Could it be that engineers at Microsoft, Oracle, and many other major companies — not to mention everyone else — have not figured out the most effective way to synchronize data access even by 2024? Is most of what programmers, including those in top IT companies (except for rare Apple platform developers), know about synchronization — wrong? Today, we will explore this in detail.

This article assumes that you already have a basic understanding of synchronization mechanisms. The code is written in C#, but the specific language is not of particular importance.

Background

I haven’t written in C# for a long time, but about 12 years ago, I began working on cross-platform mobile development using Xamarin. Tasks often required implementing various synchronization mechanisms to handle access to the state from the main and background threads, as well as synchronization for working with the SQLite database. When developing for iOS (surprisingly, many projects were iOS-only), Xamarin offered both the tools available in native development — such as Grand Central Dispatch with parallel and serial queues and NSOperationQueue based on them — and tools from C# — Monitor, SpinLock, Mutex, Semaphore, TPL Dataflow, Thread, thread-safe collections, RxUI, and much more. With such a vast variety of tools, developers used "what they could" and what they could find faster through search engines or on StackOverflow: blocking all calls from the main thread or thread pool primitives, creating separate threads, synchronization via the main thread, and the whole zoo of mechanisms I listed earlier. This occasionally led to errors like UI freezes, race conditions, or deadlocks.

But I loved getting to the heart of the matter and finding the best solution, and quickly realized that:

- Any prolonged thread blocking is bad because it either consumes CPU time while waiting in a queue or leads to context switches and additional thread creation. Blocking the main thread of an application responsible for rendering and handling user interactions is particularly bad and results in "freezing" the UI rendering and interaction handling.

- Ideally, the number of threads in an application should not exceed the number of CPU cores but should be at least two — the highest-priority one for rendering and handling interactions, and others for everything else. This minimizes context switches and memory usage.

But this doesn’t work with blocking operations — during full thread locks (Mutex), the thread pool is forced to create additional threads so that CPU cores do not idle, while during spinlocks (SpinLock), the CPU cycles are wasted. While the solution for I/O operations is obvious — use non-blocking alternatives — all the standard synchronization mechanisms in popular languages like C# block the waiting thread for the duration of the queue wait time, which can often be longer than the operation itself.

Introduction to GCD

Exploring the capabilities of the GCD library from Apple while working with Xamarin, parallel queues did not seem particularly necessary — essentially, they are equivalent to ThreadPool or TaskPool in C#.

However, serial queues caught my attention. Here’s what Apple’s documentation says about them:

Serial queues execute one task at a time in the order in which they are added to the queue. The currently executing task runs on a distinct thread (which can vary from task to task) that is managed by the dispatch queue. Serial queues are often used to synchronize access to a specific resource.

You can create as many serial queues as you need, and each queue operates concurrently with respect to all other queues. In other words, if you create four serial queues, each queue executes only one task at a time but up to four tasks could still execute concurrently, one from each queue.

They are lightweight (essentially just a list under synchronization primitives), follow the FIFO principle (first in, first out), are asynchronous — they do not block the calling thread while waiting for an operation to complete, and most importantly, they execute operations sequentially, allowing them to serve as a synchronization mechanism. They do this in other threads, without creating a thread for every operation, instead using either an existing pool or their own thread for the main thread queue (examples of usage will follow in the relevant section).

The fact that they do not block the waiting thread suggests that for lengthy operations, the best solution for synchronization is precisely serial queues. But in practice, even for the shortest operations, when developing with an existing main thread queue (e.g., on iOS), it makes no sense to use lower-level, more complex, and error-prone constructions that other team members might not be familiar with. For a nanosecond operation, it’s better to throw it into this very main thread queue, as it will have no impact on the frames per second. Moreover, practice shows that even those who think they know synchronization primitives often misunderstand them and produce poor, buggy, and slow code. Bugs in "multithreading" are often very unstable and difficult to reproduce and fix. Additionally, this approach aligns well with the commonly accepted rule of always invoking callback methods on the main thread, eliminating the need to guess which thread you are currently on and avoiding additional synchronization concerns. Incidentally, in Xamarin, for async/await calls from the main thread, this worked by default, which was quite convenient.

Real-life Examples of Thread Blocking and Synchronization Issues

Here are some real-world examples of thread-blocking errors that have impacted product quality:

-

One of the most popular car-sharing apps in Russia had its main thread constantly blocked for years, and only relatively recently did they manage to fix the issue. The app was so poorly performing that they had to retain users with the lowest prices on the market. For that, I want to thank my "clumsy-handed" colleagues — despite the suffering, the savings were significant. Their competitors, obsessed with solving algorithms on paper, seemingly out of solidarity, created extremely slow and buggy built-in car tablets, slightly "saving" the competitor's situation.

-

Do C++ developers always write the fastest applications? Here is one of the issues in the official Bitcoin wallet. The application completely freezes the interface when searching for and connecting to peers, as well as during other I/O operations. This happens quite frequently, sometimes even constantly. After a brief acquaintance with this application, I really wished someone would rewrite it using the "slow" Electron,

and the developers change their profession. That said, the void was quickly filled, and many unofficial BTC wallets were created, albeit with a lower level of trust. -

Let's not forget the backend. Many of you may have heard that PayPal rewrote its applications from Java Spring to NodeJS (as did other companies), and performance unexpectedly increased almost tenfold (2x RPS with a fivefold reduction in worker cores). Why? One of the main reasons is that Java Spring relies on blocking I/O operations (e.g., JDBC doesn’t have a non-blocking interface at all) and blocking synchronization mechanisms. This approach, in addition to significant resource overuse, introduces bugs that affect application stability, such as this one. When I realize the engineering nightmare of current backend development standards in Java (sometimes mitigated with hacks like Loom), I hope technologically advanced aliens don’t exist — if they see what we’re doing here, they’ll consider us a failed species, and there will be no mercy. Incidentally, it's not just about performance — according to PayPal, development speed significantly increased, code volume decreased, and team size was reduced. This is unsurprising; looking at how the same task is implemented on these two technologies, I recall the joke about removing tonsils through the rectum.

-

And now for something personal and painful: SourceTree on Mac. Once, before Apple abandoned skeuomorphism, I considered it the best app on my MacBook — very convenient, fast, and responsive. But after the appearance of new, flat design guidelines, it seems (in my theory) that, along with the redesign, it was decided to rewrite everything "from scratch" with a new team (I see no other reason), and since then, for many years, hardware has been getting faster, but SourceTree still "freezes" the main thread and works slower than it did 10 years ago on an old MacBook Air.

-

It would be a sin not to

shoehorn incompare the performance of two competing operating systems: Apple’s iOS, where these queues were invented and used, an epitome and role model in terms of OS performance, UI responsiveness, and battery consumption (at least in the past), and Google’s Android — the same but the opposite (at least in the past ©). Those who owned both an iPhone 3GS (600MHz, 256MB) and an LG GT540 (600MHz, 256MB) "cannot find words to describe the pain and humiliation" experienced with the latter, even after installing a custom Android 4.4 and overclocking it to 800MHz (ah, those were the days). Meanwhile, the former showed no freezes or lags (until planned obsolescence arrived with a new update). And Android devices’ batteries were the main driver for increasing device size. Over time, hardware improved, smartphones became hand-unfriendly with 4+ cores and 8+ GB of memory, and life became somewhat bearable. Yes, the standards for developing client apps and OS in Java haven’t strayed far from the backend, and Apple's decision against using Java in iOS cannot be overstated.

As we can see, this is indeed an important topic that directly impacts the quality and user experience of client applications, as well as the performance, stability, and cost of infrastructure for server-side applications.

What’s the Problem?

Strangely enough, the standard libraries of many programming languages — both back then and now — despite the variety of synchronization tools, do not include this solution out of the box, even though it’s very simple to implement using existing tools. For example, in C#, it can be done via SemaphoreSlim, ActionBlock, or simply chaining tasks together. Moreover, Microsoft felt that something like this was needed and created a class with the awkward name SynchronizationContext. However, they failed to fully develop the idea or use it as a foundational synchronization mechanism. Could we have had a SerialTheadPoolSynchronizationContext? No, SerialQueue sounds much better.

Even on Apple’s platform, where these queues originated, the most popular SQLite library (with around 10k stars) uses queues but in a blocking mode, nullifying all their advantages. Moreover, even experienced native iOS developers often consider queues to be heavy and believe that a skilled developer should use synchronization primitives because they are much faster. In reality, they often work much slower than queues, which many find hard to grasp. Even during interviews at top tech companies, I got tired of arguing about this and found it beneath me to answer questions the way interviewers expected just to pass their filters.

Writing a Library

After finishing my work with Xamarin about 8 years ago, I wrote my own implementation of serial queues for synchronizing data access in C#, to fill the gap for all other platforms of the C# language, which, unfortunately, only Apple had managed to figure out (perhaps somewhere else and much earlier—feel free to share in the comments).

Only recently, many years later, after yet another discussion with a developer who decided I was spouting nonsense and after receiving yet another downvote on StackOverflow, I decided to finally write a load test to validate my beliefs and to reference in future discussions. Especially since those who have seriously engaged in optimization know that even obvious improvements can often make things worse in practice, so testing hypotheses is always better. At the same time, I wrote a lighter implementation that doesn't use Task.

Usage Examples

Let’s consider its usage with an example of a request handler based on Task, and here is example with the familiar Monitor:

readonly object locker = new object();

// This function is called concurrenlty in the thread pool for each request

async Task<Response> HandleRequest(Request request) {

...

lock(locker) {

// Processing the state requiring synchronization

}

...

}

Here’s the same code using a SerialQueue based on Task:

readonly SerialQueue serialQueue = new SerialQueue();

// This function is called concurrenlty in the thread pool for each request

async Task<Response> HandleRequest(Request request) {

...

await serialQueue.Enqueue(() => {

// Processing the state requiring synchronization

});

...

}

Now let's look at a request handler based on callback methods. Here’s the implementation using Monitor:

readonly object locker = new object();

// This function is called concurrenlty in the thread pool for each request

void HandleRequest(Request request, Action<Request, Response> next) {

...

lock(locker) {

// Processing the state requiring synchronization

}

...

next(request, response);

}

Here’s the same code using a lightweight SerialQueue (not based on Task):

readonly SerialQueue serialQueue = new SerialQueue();

// This function is called concurrenlty in the thread pool for each request

void HandleRequest(Request request, Action<Request, Response> next) {

...

serialQueue.DispatchAsync(() => {

// Processing the state requiring synchronization

ThreadPool.QueueUserWorkItem((object? _) => {

// Continuing work in the thread pool

...

next(request, response);

});

});

...

}

Performance Test Results (Apple M1, 16GB)

Table of Results (in CPU ticks — the fewer, the better):

| Operation duration, ms | 0.0001 | 0.0005 | 0.001 | 0.005 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 50 | 100 | 500 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SpinLock | 15.24 | 21.62 | 3.98 | 13.24 | 86.78 | 114.53 | 245.26 | 902.28 | 1802.06 | 4031.45 | 3689.18 | 42148.81 | 144129.48 | 74526754.36 |

| Monitor | 38.06 | 80.96 | 132.52 | 303.65 | 344.67 | 674.58 | 745.05 | 1282.7 | 2159.8 | 3523.11 | 2512.77 | 12459.23 | 25018.15 | 42703.06 |

| Mutex | 2042.54 | 2039.1 | 2085.99 | 1961.65 | 2341.45 | 2003.45 | 2141.01 | 3264.76 | 4357.84 | 7597.05 | 10985.34 | 23886.55 | 24894.28 | 38406.99 |

| SemaphoreSlim | 1885.55 | 1965.17 | 1464.16 | 1452.77 | 1321.23 | 1771.67 | 2192.26 | 7127.71 | 8375.92 | 9425.43 | 8627.65 | 10208.14 | 11139.17 | 12852.06 |

| TPL Dataflow ActionBlock | 500.46 | 379.06 | 389.52 | 356.72 | 398.81 | 543.16 | 654.34 | 758.73 | 773.72 | 965.08 | 1409.53 | 3062.4 | 3809.25 | 4511.62 |

| SerialQueue (by @borland) | 6539.76 | 7389.57 | 9070.94 | 9596.84 | 9621.69 | 9819.38 | 10020.03 | 10843.35 | 11091.59 | 7834.07 | 5726.59 | 2757.34 | 2736.65 | 4605.69 |

| SerialQueue (Task-based) | 328.58 | 437.86 | 367.49 | 399.73 | 421.17 | 458.2 | 521.24 | 513.98 | 530.65 | 384.38 | 532.93 | 2411.29 | 2839.88 | 5261.37 |

| SerialQueue | 32.74 | 73.67 | 100.93 | 110.67 | 158.19 | 138.72 | 311.52 | 297.83 | 340.75 | 158.78 | 277.85 | 292.75 | 194.22 | 324.22 |

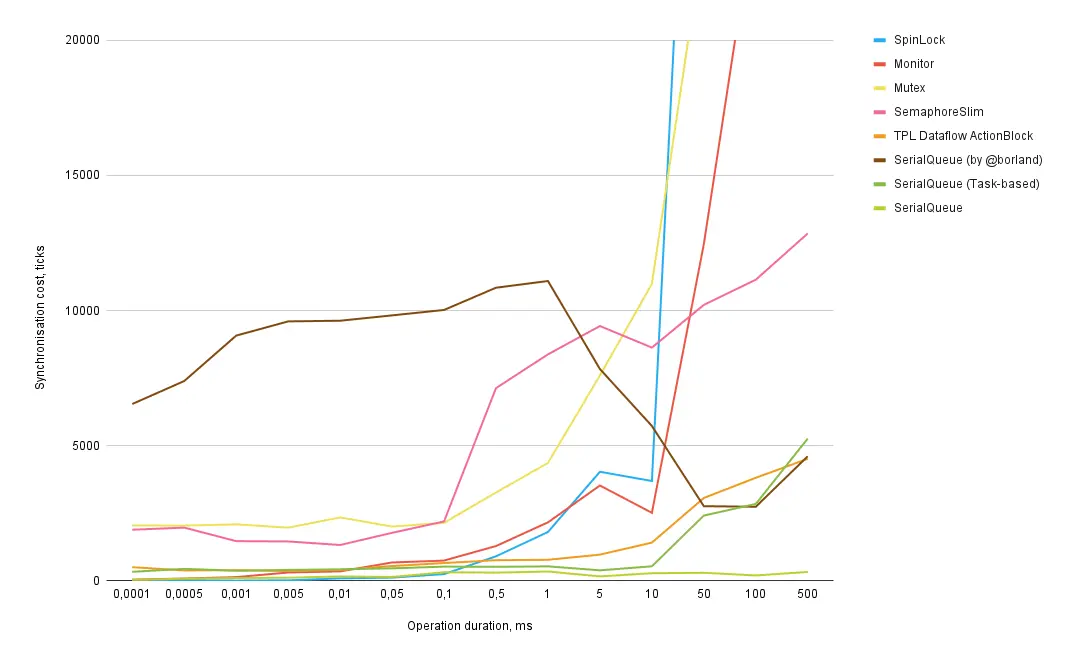

Graph 1: Approximate synchronization overhead depending on operation duration (the lower, the better).

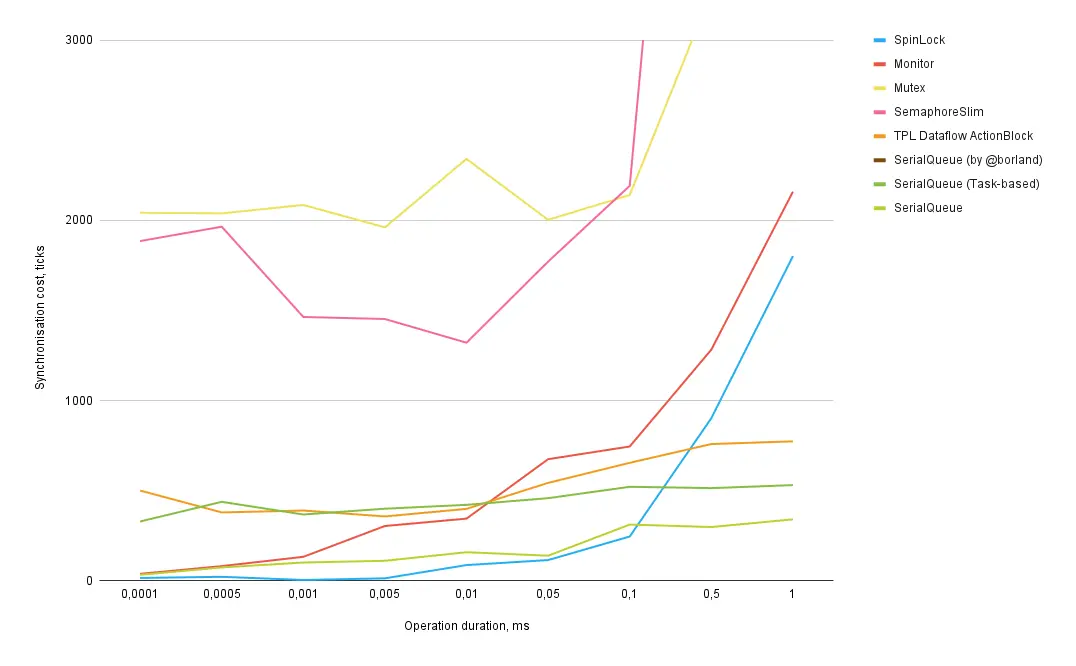

Graph 2: Zoomed-in view (the lower, the better).

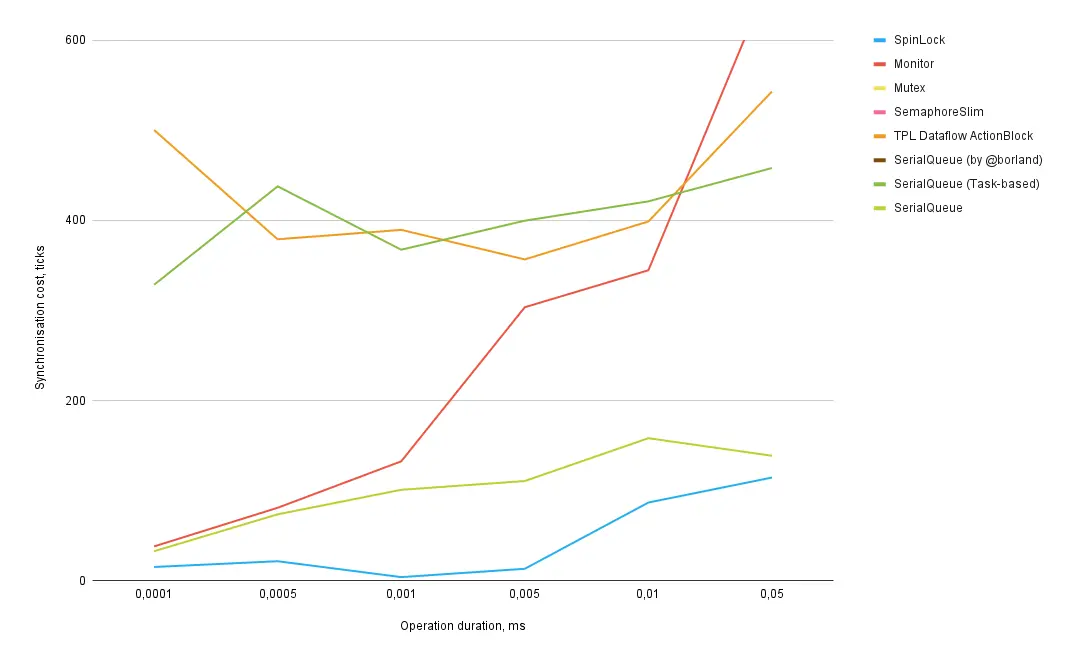

Graph 3: Zoomed-in view for the shortest operations (the lower, the better).

The number of iterations for measurement decreases as the operation duration increases, so the accuracy for longer operations is lower than for shorter ones. Otherwise, the tests would have taken several days to run.

X-axis — duration of the synchronized operation in milliseconds.

Y-axis — approximate synchronization overhead in processor ticks.

Synchronization mechanisms:

- SpinLock, Monitor, Mutex — standard synchronization primitives.

- SemaphoreSlim — a simplified alternative to

Semaphore. It is the top-rated answer on the corresponding StackOverflow question. - TPL Dataflow ActionBlock — a queue implementation using TPL Dataflow

ActionBlock. - SerialQueue (by @borland) — a similar queue implementation by GitHub user @borland, available on NuGet. Included for comparison.

- SerialQueue — my lightweight serial queue implementation.

- SerialQueue Tasks — my task-based serial queue implementation.

Example of reading graphs:

- Synchronizing an operation that lasts 0.001 milliseconds incurs an additional 4 processor ticks for SpinLock, 133 for Monitor, and 101 for SerialQueue.

- Synchronizing an operation that lasts 100 milliseconds incurs an additional 144,129 processor ticks for SpinLock, 25,018 for Monitor, and 194 for SerialQueue.

Key insights from these results:

-

The most efficient synchronization method for operations up to 0.1 milliseconds is SpinLock. SerialQueue is the second most efficient. It’s surprising that SerialQueue even outperformed Monitor for all tested operations. Let’s consider them roughly equal for operations under 500 nanoseconds, beyond which the queue becomes preferable.

However, keep in mind that operations shorter than 100 nanoseconds were not tested — at such scales, the overhead of the test itself would exceed the operation's duration. Separate tests would be needed for these cases, but the results are unlikely to differ significantly. -

For operations longer than 0.1 milliseconds, SerialQueue is the most efficient.

-

My Task-based queue implementation outperforms SpinLock for operations lasting over 0.5 milliseconds and Monitor for operations over 0.05 milliseconds.

-

The performance of blocking synchronization primitives significantly degrades as operation duration increases. For operations of 500 milliseconds, I had to truncate the graph since synchronization overhead exceeds 7×10^7 ticks.

-

Monitor outperforms SpinLock only for operations lasting 5 milliseconds or longer. However, this is irrelevant since queues are far more efficient for such durations. Interestingly, for my queue implementation without Task, Monitor performed slightly better or at least not worse.

-

Mutex and SemaphoreSlim are less efficient than other methods for any operation length.

-

A similar SerialQueue implementation by GitHub user @borland performs the worst by a wide margin until it catches up with

Task-based queuescloser to 50 milliseconds. Notably, it doesn’t use Task.

It is also important to emphasize once again that with blocking methods (e.g., SpinLock, Monitor, etc.), the costs of synchronization and performing the operation are entirely borne by the calling thread. In contrast, for non-blocking methods (SerialQueue), the calling thread is only blocked for the time it takes to add the operation to the queue, while the remaining costs and the operation itself are handled in the thread pool. This provides even more advantages for queues when working from the main application thread.

Conclusions

So, what is the correct approach to use for:

-

Synchronizing operations with SQLite?

- Use queues, as operations generally take significant time.

-

Synchronizing application state in memory, when it is often necessary to read and modify data across multiple collections in a single transaction? This may even involve using immutable data structures, copying them during modifications to enable reading from any thread without issues.

- Use queues for the same reason as above.

-

Simply incrementing a counter or updating a reference?

- If a sequential queue (e.g., a main thread queue) is already available and the operation is not called thousands of times per second, avoid complicating the code and use the existing queue.

- Only if there is no pre-existing queue, use lightweight blocking synchronization mechanisms such as

SpinLock,Interlocked, etc.

-

If you're unsure about operation duration and the number and length of synchronized operations may change in the future?

- queues, as their performance does not degrade with operation length (O(1)), while remaining highly efficient even for short operations.

However, it’s crucial to acknowledge that serial queues are an asynchronous synchronization mechanism because an effective, non-blocking synchronization mechanism for lengthy operations cannot be synchronous. Not all programmers are ready to write asynchronous code, and not all languages and frameworks make this easy. It’s better to avoid languages and frameworks that lack convenient asynchronous functionality. Unfortunately, even with convenient async (without "callback hell"), there’s often a cost, as seen with Task in C#. This cost could have been avoided if async/await were translated into callbacks. However, on Apple platforms, developers are already accustomed to callbacks, and queues are used regularly. Even in C#, the cost of Task becomes negligible for operations longer than 0.05 milliseconds compared to Monitor, as shown by the tests.

Another point to note: synchronization mechanisms are not always the primary bottleneck, even in the examples discussed earlier. The main law of modern software development has long been clear to me: "Even bad code works just fine" (albeit not as well on low-end devices with drained batteries). This is just a small part of the enormous codebase that could perform better. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t know, learn, and strive to do things the best way possible.

What About Concurrent Collections and ReaderWriterLock?

Thread-safe collections should also be discarded, as they are only suitable for Hello World-level applications. They are implemented using blocking synchronization methods and also provoke race condition bugs when you need to synchronize access to multiple collections in a single transaction or perform several operations on one. It’s always better to use non-thread-safe implementations of any logic and wrap their usage in a synchronization mechanism that fits best. This approach also avoids bugs like deadlocks since there will be no nested synchronizations.

ReaderWriterLock also seems useless to me. First, the approach using immutable data structures allows them to be read from any thread, and a simple queue can suffice here. Second, if you use mutable structures, I believe implementations of ReaderWriter[Serial]Queue and ReaderWriterSpinLock would be far more efficient. But I won’t write these implementations or verify this hypothesis.

Epilogue

How is it possible that such fundamental concepts are practically unknown? Why do developers in leading global IT companies continue to write more and more subpar code like Concurrent Collections instead of adding and advocating for better synchronization methods? I would say that truly skilled developers are few and far between. Most are limited to solving LeetCode-style tasks and blindly using the most popular frameworks. Then the same people conduct interviews, hiring those like themselves. Some become CTOs and promote outright poor technologies in the largest companies, producing developers trained on these technologies.

Let’s admit that most of those reading this article have never even heard of serial queues, and many would even demand answers during interviews that contradict what’s written here.

That said, there are positive trends in addressing blocking issues:

- Green threads.

- The absence of synchronization tools, restrictions on cross-thread data access, and [almost] enforced asynchronous I/O operations (e.g., NodeJS).

It turns out that teaching the average leetcode-driven developer proper multithreading practices is nearly impossible. Everything is moving towards eradicating this problem entirely, albeit at the cost of slight performance degradation (direct, skilled work with thread pools and effective synchronization mechanisms will always be faster). Virtual threads, virtual DOM—what’s next?

What I’d recommend to people making architectural decisions:

- Choose technologies where "smart folks" have thought everything through, and such issues are practically nonexistent, e.g., TypeScript (NodeJS, React Native, Electron, etc.), Go (green threads), and so on.

- If the first option is not feasible for some reason, share a link to this article. Maybe, at last, this knowledge will no longer be hidden, and there will be someone to discuss it with on equal terms. I look forward to constructive comments.